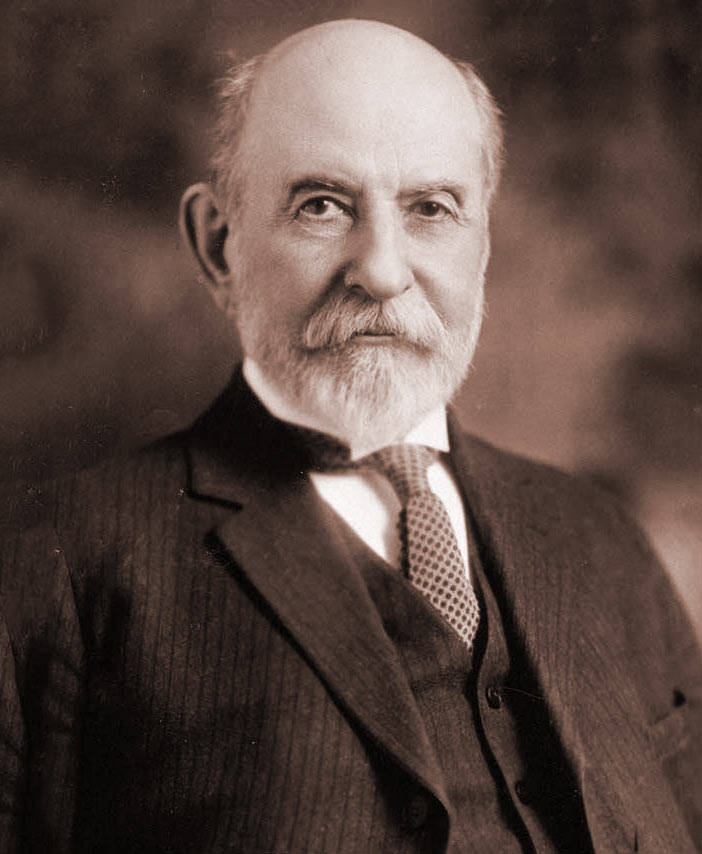

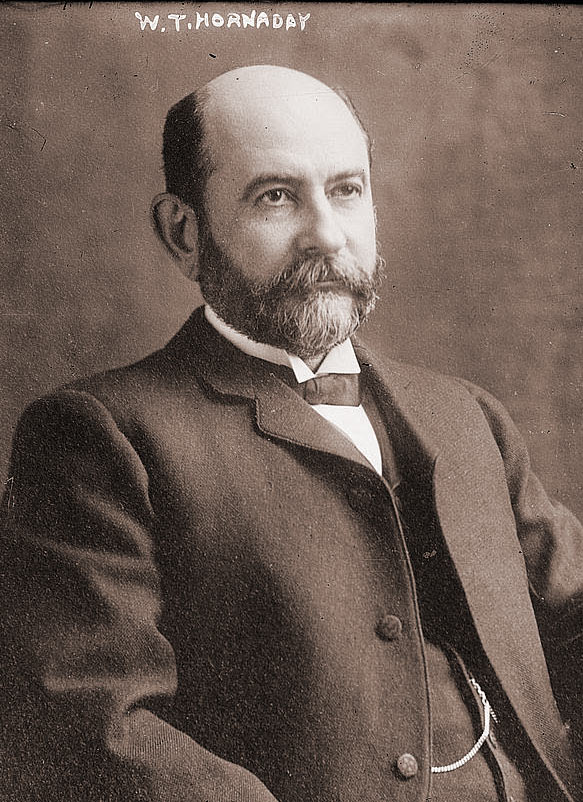

Date of Birth: December 1, 1854

Place of Birth: Avon, Indiana

Date of Death: March 6, 1937

Place of Burial: Greenwich, Connecticut

William Temple Hornaday was an American zoologist, conservationist, taxidermist and author. Born in Avon, Indiana on December 1, 1854, he died in Stamford, Connecticut on March 6, 1937 and subsequently buried in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Many taxidermists are familiar with the mail order taxidermy lessons from the Northwestern School of Taxidermy, in Omaha, Nebraska. Fewer know that the lessons were taken from the book, Taxidermy and Zoological Collecting (1891), of which William T. Hornaday is the author. The availability of these lessons in their day resulted in many wildlife enthusiasts learning the fascinating art of taxidermy.

William T. Hornaday learned taxidermy while apprenticing at Henry Augustus Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York, in the early 1870’s. Possessed with natural talent, he excelled at Ward’s and by his mid-twenties he was promoted to head taxidermist. It was during this time that he wrote the first substantial book on taxidermy procedures. He helped to organize the Society of American Taxidermist in 1880. All of this, incidentally, occurred two years before Carl Akeley would start working at Ward’s.

In 1882, he was appointed chief taxidermist of the United States National Museum (Smithsonian Institute) until he resigned in 1890. He went on to found the National Zoo in Washington D.C. and next served as the Director of the Bronx Zoo for thirty years.

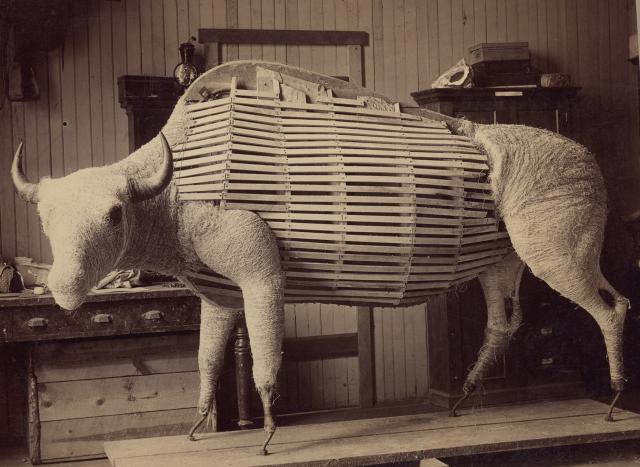

As well-known as he was for taxidermy, he was a major figure in the modern conservation movement. While director at the National Museum, he took on the task of inventorying the museum’s specimen collection, particularly their American Buffalo specimens. He found that there were so few that he took on the task of taking a census. He estimated that in 1867 there were approximately 15 million bison in the West. During a collecting trip to Montana in 1886, he witnessed one of the last surviving herds numbering only around 100. Some of his bison mounts, which were collected on that trip, remain on display today at the Museum of the Northern Great Plains in Fort Benton, Montana.

Hornaday was responsible for bringing live bison to Washington D.C. which were the precursor to the National Zoological Park’s thriving herd. It was surplus animals from this group that a wild herd was established in the Wichita National Forest and Game Preserve in 1919. These conservation efforts were supported by Theodore Roosevelt and the Society for the Protection of the Bison.

The Hornaday Bison Group, as it was known, became famous and the big bull was the model for the artwork on the 1901 ten-dollar bill as well as the buffalo on the Indian head nickel. The group was displayed in the Smithsonian until 1957 when it was dismantled 21 years after his death. When the plaster groundwork was broken up, workers discovered a time capsule placed in a metal container buried within the habitat. Inside was a magazine account of the buffalo hunt written by Hornaday as well as a personal letter to his successor, the unknown future chief taxidermist of the museum. The letter read:

“Dear Sir,

Enclosed please find a brief and truthful account of the specimens which compose this group … killed by yours truly. When I am dust and ashes, I beg you to protect these specimens from deterioration and destruction. Of course they are crude productions in comparison with what you [now] produce, but you must remember at this time (AD 1888), the American school of taxidermy has only just been recognized. Therefore give the devil his due and revile not.

—WTH”

To honor his request, the group was saved from destruction and sent to Montana, where they were placed in storage. After many years of neglect, they were rediscovered, restored, and placed on display in 1996 at the Museum of the Northern Great Plains in Fort Benton, Montana, where they stand today.

A year after his death, in 1938, at the suggestion of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the National Park Service named a peak, Mount Hornaday, in the Absaroka Range in Yellowstone National Park for him.