Date of Birth: April 28, 1882

Place of Birth: Dowagiac, Michigan

Date of Death: September 18, 1975

Place of Death: Aurora, Illinois

Leon Luther Pray was born April 28, 1882 in Dowagiac, Michigan. His father, Luther J. Pray, was a civil war veteran and a local businessman. His mother, Ellen Cardey Pray, had been a school teacher and was a homemaker. Leon was the third child and only son in a family of four children.

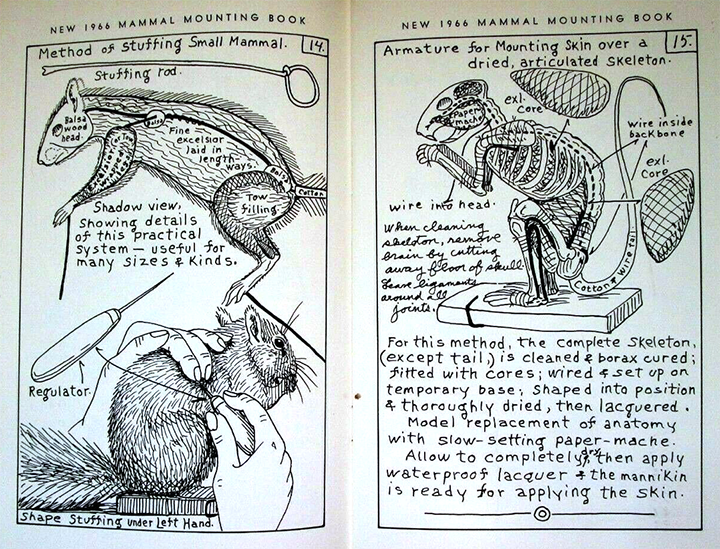

Leon grew up to become one of the few most influential and respected professional taxidermists of the twentieth century, most notably due to his written work and the products of his nearly 45 years of association with The Field Museum of Chicago. His artistic skills were not limited to taxidermy: He was proficient from early childhood at pencil sketching the world around him, with special emphasis on the creatures inhabiting it. He subsequently expanded his mastery to painting, sculpting, modeling, carving and illustration.

Captivated by nature, Leon spent as much of his boyhood as possible exploring the hills, fields, lakes and streams of his South-West Michigan area. His artistic nature was fired by these ventures.

In 1893, Leon accompanied his parents to Chicago to attend the World’s Columbian Exposition (The Chicago World’s Fair) in Jackson Park. Leon was especially impressed by the Palace of Fine Arts, with its collection of mounted animals from throughout the world. He had seen some taxidermy exhibits at the county fairgrounds, but what he saw in Chicago far overshadowed the local efforts and planted the seed to become a taxidermist himself.

From the age at which he could build cages for and feed them, Leon had kept a little menagerie of small mammals and birds in the back yard at home. He was always busy, sketching these creatures in myriad poses, becoming familiar with their bone, muscle, skin, hair and feather features in the process. Many young boys were attracted by this activity and Leon acquired his first mounted specimen, a woodchuck that one of the boys brought with him as “trade goods.”

Leon got an airgun and began collecting birds, chipmunks and gophers. He paid a local taxidermist $1.50 to mount a redwing blackbird, the beginning of his collection. He added several more birds in this way, but it was too expensive for him to keep up. He still wanted to learn taxidermy for himself.

At this point, Leon was thrilled to learn that an old family friend, the Reverend J.B. Tallman, a circuit-riding preacher, was coming to town for a week to fill the empty pulpit of the Methodist church the family attended. In addition to being a minister, Tallman was also a taxidermist! During the week, Tallman came to dinner at the Prays’ and Leon showed him his small collection of dearly-bought mounts.

Tallman laughed at them and proceeded to twist them into different shapes, breaking bones and cracking dry skin as he did so. Leon was horrified. He wrote later, “Of course he had a right to criticize, for he (the local taxidermist) was not a stuffer of wide repute. “But, my gosh, who gave him the right to bust up my hard-earned specimens? He smashed them all, saying that the man who mounted them knew nothing about nature at all. I felt fit to be tied!”

“When I could get my breath, I told the old gentleman about my wish to learn to stuff birds. “He thereupon offered to stuff a bird for me if I would bring one to the parsonage on Saturday. “I was there, you may be sure, with a bluejay shot on Friday evening after school.”

“My fellow taxidermists will have no difficulty in picturing the thrill of those rare moments as I watched every movement of the old man’s skilled hands at work on that bird-mounting job. “Every phase of the scene is still clear in my memory.”

“The few years that followed were illuminated by activity in a tiny work-shop partitioned by my father off in a corner of our barn loft, where every spare moment I plugged away, mounting every bird or small mammal I could come by. During this time, my “zoo” furnished a specimen now and then through decease.

“In these brief years I became so fond of taxidermy that I had visions of someday going to work for the museum in Chicago, which had been organized sometime after the conclusion of the 1893 World’s Fair.”

On Saturday, June 2, 1894, the Field Museum in Chicago was opened in the old Fine Arts building of the Fair, in Lincoln Park. When Leon read about it in the local paper, he told his mother that he was going to work in that museum someday. He was twelve years old.

In 1898, Leon’s father, Luther, sold off his business and headed North for the Klondike gold rush, to make his fortune. Gone for two years, he returned poorer but wiser and re-entered the local business community. While he was away, Leon’s mother, Ellen, took in roomers to make ends meet. She tried to get Leon to contribute to the family finances, but by then he was frustrated with school and uninterested in work.

She fretted, in a letter to Luther in Skagway on 9-9-00 that, “I am going to keep watch of his school work and if he does not do better than he has other years he shall quit school and go to work…” She concluded, saying “He does not appreciate his talent in drawing as he ought and I am so afraid he never will and that all will be wasted…”

In November of 1901, Leon’s dream of working at The Field became a reality; it happened this way: Leon did leave school and two of his teachers, most notably Grace Gildersleeve Duncan, who had shown special interest in his artistic ability, took him to Benton Harbor to a lecture on art and sculpture by the renowned sculptor and artist, Lorado Taft. Leon showed Mr. Taft a sheaf of his animal drawings and told Taft of his interest in taxidermy. Taft told him to write to Carl Akeley at The Field Museum and see what he would say. Leon did so and received an answer to see Akeley the next time he was in Chicago.

The opportunity came, as mentioned previously, in November of 1901. Mr. Akeley offered to pay Leon $30.00 for a month’s trial to see if he could qualify as a special small mammal taxidermist. As Leon’s month drew to a close and Akeley was about to send the young apprentice on his way, Leon mounted a fox squirrel scratching its shoulder with a hind foot. Akeley beamed when Leon showed the squirrel to him. He then arranged a stipend from the office to keep Leon around for further tests. Time went on and Leon was told he might remain but, due to cool relations between Akeley and the front office, Leon should not expect a fat salary. In fact, he truly would literally have to live on the love of the work. Akeley’s own annual salary then was $3,000.00 and Leon was just a beginner.

Leon stayed at The Field amassing experience for 3 ½ years. He worked under Akeley studying and adding to the Akeley method of large mammal mounts until the spring of 1905 when Akeley made preparations to leave for a second African collecting trip. The taxidermy division was to be closed for the time being. Leon faced an unsure future as Akeley prepared for departure. Leon told his boss that he was going to leave, too. By March, Leon was briefly back in Dowagiac, preparing to see if his future lay in the West, as Horace Greeley had urged young men, some years earlier.

In May of 1905, Leon set out by train from Dowagiac to Newcastle, California. There he worked for a time in a fruit cannery owned and operated by family friends. On 8-13-05 he shot the only deer of his lifetime in the American River country of El Dorado County. The mounted rack and a hoof and a number of water color paintings and small sketches from this time survive. Leon also worked in a hotel in Santa Barbara and visited San Francisco twice. After five months, Leon was convinced the opportunity he’d sought to employ his skills didn’t exist on the West Coast.

In October of 1905 Leon returned to Dowagiac for about a year, during which no favorable local prospects developed. In November of 1906 he left by train for Mandan, North Dakota, to work for well-known commercial taxidermist J.D. Allen. Leon mounted birds while Allen did the larger game. In the spring of ’07 Leon returned to Dowagiac and an aunt staked him to a course of study at the Chicago Art Institute. While there, he received word that The Field’s staff artist had died and the position was vacant. He applied and was accepted. He continued to attend the Art Institute on evenings and Saturdays until 1909. Leon was to remain at The Field for 41 more years, retiring at last in 1948 with a total of near 45 years of service.

In 1908, Leon married Marie Sauter, who was part owner of the restaurant in Chicago where he took his meals. Their only child, Ellen Karlena, was born to them on November 9, 1911 in Dowagiac. While living in Chicago, Leon earned extra income to support his little family doing commercial work out of a shop in the spare bedroom of their flat. He particularly catered to customers of Von Lengerke & Antoine’s (VL& A’s), an upscale sporting goods emporium in Chicago. In 1913 the Macmillan Company published Leon’s landmark book, Taxidermy, which went through numerous editions until it was completely revised in 1943. Leon notably did the animal illustrations for the Thorndike Century and Random House American College dictionaries, among other commercial illustration and art work jobs.

While at The Field, Leon also developed the non-poisonous Borax Solution Mothproofing process to replace the Arsenic system that had been poisoning the taxidermists right along with their moth and dermestid targets for years. Leon also developed direct-built, large mammal mannekins; incredibly detailed and lifelike fish models to replace skin mounts almost universally doomed to deterioration; hollow, built-in small mammal bodies; perfected bird-mounting methods; a radical, new method of skinning and mounting turtles and tortoises; a sand-fill method for mounting non-greasy, hard-scaled fish; a casein paint compo. for modeling and sculpting; a plaster-mould casting separator possessing ideal qualities and a perfected modeling tool easily produced by the artist.

Leon was appointed Zoological Preparator of Fishes for The Field in 1939. The entire former Hall of Fishes was nearly all his work, including the breathtaking Bahama Reef Group which he personally collected in the Bahamas in 1929. This magnificent display is, today, tucked away in a corner of the Harris Educational Loan Center at The Field. In addition to the Bahamas expedition, Leon took part in eight other collecting trips for The Field.

In the words of a friend and colleague, the late John W. Moyer, “Leon Pray was an all-‘round taxidermist; not only skilled in the art of taxidermy, but an artist, sculptor, craftsman (in many mediums) and author – all needed with some degree of skill to be successful in taxidermy. Pray’s work while at Field Museum was in all branches of the art; birds, small and large mammals, fish, reptiles and as a background artist. Pray was prolific and wrote many pamphlets and books on the subject of taxidermy.”

These books and pamphlets most notably came from Leon’s 1937-1975 association with Joseph Bruchac and the Modern Taxidermist Press of Greenfield Center, New York. Mr. Moyer goes on to note that “I was fortunate to be at Field Museum when Pray was experimenting with borax mothproofing and I can say now that from the results I witnessed and that he worked out at the same time, if one follows his instructions, borax will do the job in the preservation of fresh skins for mounts.”

Further evidence of Leon’s skills and far-reaching abilities are the production of life-size models of Mesembriornis and Coelacanth and a display featuring casts of his own hands showing the flint-knapping technique of native Americans in producing stone and flint tools and weapons. In preparation for this latter exhibit, he taught himself the processes and made his own tools, faithful to the originals. All these last three projects were undertaken and completed during his last decade with the Museum.

Following his retirement from The Field in 1948, Leon L. Pray moved to San Diego, California and spent nearly two years there helping to restore the San Diego Natural History Museum from its service during World War II as a Naval Hospital. In 1950, he returned to Illinois, making his home in Aurora, near and then with his daughter for the last 25 years of his life. During this time, he served as an on-call consultant for the Field, helping with instruction in taxidermy techniques and background painting. He also served as the “corporate memory” as to how to safely move Akeley’s elephants during renovation of the Stanley Field Hall in the ‘60s.

After he retired, Leon maintained a thriving business in the sale of fish color charts and life-sized mammal body patterns. He sold off the body patterns business in the ‘sixties, but continued to produce the fish color sketches until age and infirmity caught up with him in 1970. Things were never the same again for Leon after he lost his beloved wife Marie (“Peepsie”, he called her affectionately) in the summer of 1967. Leon died on September 18, 1975, in Aurora. He was in his 93rd year.

In concluding this biographical sketch, the words of his friend John Moyer are, once again, fitting: “Leon L. Pray (is) a name associated with the art of taxidermy for many years. It is most certain that nearly all who today practice taxidermy have heard of and are acquainted with the craftsmanship, drawings and writings of this man. His name is to this generation of taxidermists what the name of Carl Akeley was to those of a generation ago. Pray’s work will live for many years as natural history exhibits in the Field Museum of Natural History where he spent so many fruitful years of his life ….A former director of Field Museum said of Leon Pray, ‘He was a genius,’ — and he was.”

Compiled by Lee E. Goewey, grandson of Leon L. Pray, 2-10-2005

Biography reprinted from Taxidermy.net

https://www.taxidermy.net/threads/245502/